|

So, I picked this book up because it reminded me of another book I enjoyed which was How the Irish Saved Civilization (by a different author, Thomas Cahill I think?). It's the theme of a culture, usually through diaspora, sharing literature/philosophy/art, etc.

With the Irish book, the argument is that because Irish monasteries housed writing and not gold, they were often repositories of knowledge lost by other European countries during the Medieval ages. Only through the diaspora and inclusion of Ireland (usually via British invasion) was this knowledge dispersed. Granted, it wasn't like the Middle East, Asia, Africa, or the Americas were wandering around clueless...they also had a strong literary tradition of all this stuff, but still. This book is more on Philosophy and Education that was passed through Scottish diaspora. I took a lot of philosophy courses in college, so this wasn't totally new to me, but I think it can be a bit dry if that's an uninteresting subject. I thought it was really interesting but I'm a huge nerd. The Scottish diaspora was in tandem with the Highland clearances and with the British Empire "colonizing" the world. Colonizing or you know...invading. NPR did an interview with Arthur Herman, which I managed to embed. I love NPR. Herman was a coordinator of the Smithsonian's Western Heritage Program. He now a senior fellow at a Think Tank called the Hudson Institute. Think tanks can be full of brilliant people or morons. The Hudson Institute is a conservative think tank that writes semi-interesting reports and blows smoke up conservative men's assholes. So... the norm I suppose. No, seriously, look at who they give awards to and then tell me I'm wrong because I am not. I live and work around politicians. They need a lot of smoke blowing. A small, select few need to be put in a padded room. We don't have to name names. We all know who.

Title: How the Scots Invented the Modern World: The True Story of How Western Europe's Poorest Nation Created Our World and Everything In It

Author: Arthur Herman Page Number: 472 pages (paperback) Genre: History, Nonfiction Publisher: Three Rivers Press, part of Random House Year: 2001

Who formed the first literate society? Who invented our modern ideas of democracy and free market capitalism?

The Scots. As historian and author Arthur Herman reveals, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Scotland made crucial contributions to science, philosophy, literature, education, medicine, commerce, and politics—contributions that have formed and nurtured the modern West ever since. This book is not just about Scotland: it is an exciting account of the origins of the modern world. No one who takes this incredible historical trek will ever view the Scots—or the modern West—in the same way again.

The book begins with John Knox and the Scottish "reformation." The Scottish Reformation and Enlightenment highlighted the importance of education for the Scottish people. While the nation itself was quite poor compared to other nations (France, Poland, etc.) it was the first modern literate society. Around 75% of males in Scotland could read in 1750, an unheard-of number in comparison to other European nations.

The unification between Scotland and England/Wales happened underKing James I/VI, this allowed wealth and opportunity for both nations and led to the Scottish Enlightenment. Many of the early chapters of the book deal with the key players of the Enlightenment (Francis Hutcheson, Adam Smith, David Hume, William Robertson, etc.) and there is a breakdown of many of the philosophy they created. It can be a tad dry, but since it forms quite a huge aspect of not only the educational aspects of several other countries and the basis of many economic theories it is worth knowing.

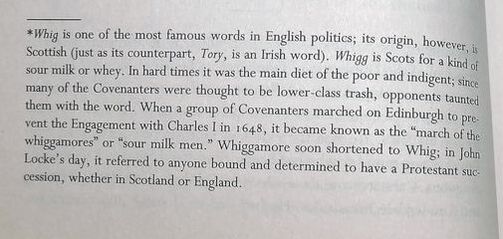

There are extensive footnotes, that are huge fonts of knowledge. The UK has several political parties through time, and the Whig and Tory parties make several huge plays in their history.

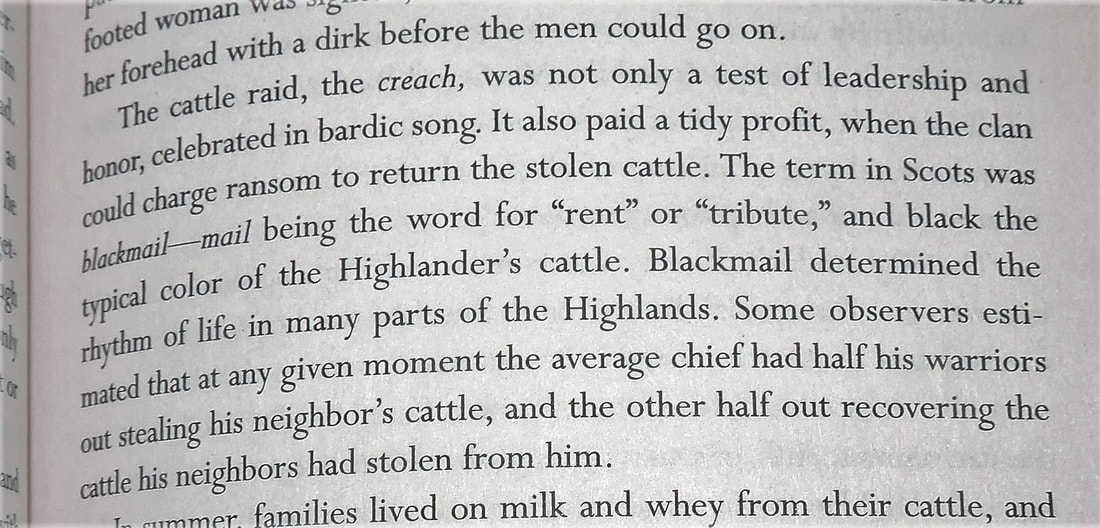

There is also a section on Scottish history of the time. The Scoti/Gael origins all the way through the modernization under the British. Some huge events, such as Culloden, the escape of Bonnie Prince Charlie, the Clan and Tartan history, and the (non)mythos aspect of the feared highland warrior. Many of these highlanders would fight for other nations for money and were feared (like the Irish Gallowglass).

The Jacobite cause has been romanticized through literature (and other art forms), but it was all shades of gray in real life. I believe there's an entire chapter that breaks down Culloden, Flora MacDonald, Bonnie Prince Charlie, and the Scottish "cause."

Culloden was really a turning point. It was the final hurrah for the Jacobite rising. After 1745, commerce exploded in cities like Glasgow, with huge amounts of money coming into the coffers of trade and tobacco merchants. What I found truly interesting, was the time spent waiting for shipments to come in. It created an idleness not seen before in merchants. Many men and women in the newly affluent merchant class took or audited classes at the universities in town. This created a coincidental links between commerce and education.

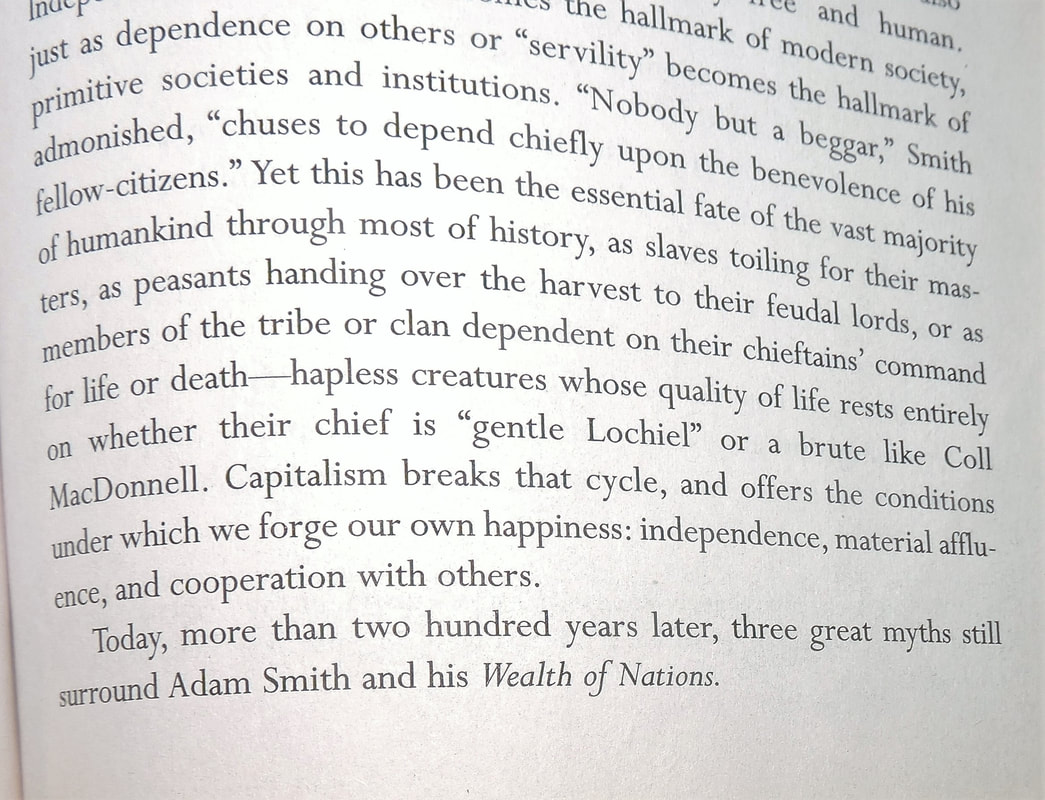

Adam Smith learned at the University of Glasgow before moving on to Oxford. He learned under David Hume and studied Francis Hutcheson. Adam Smith eventually returned to the University of Glasgow as the Chair of Moral Philosophy where he taught many students a behavioral philosophy or what turned into the modern economic theory that is still studied today. Smith's economic theory is multi-faceted and not understood by many that quote it (I said what I said!). I found the book interesting in the breakdown of Smith's view of capitalism because I think Herman really detailed the nuances of Adam Smith's Division of Labor, outlined in his Wealth of Nations. Later in the book, Herman breaks down the "myths" surrounding Smith's work.

The section after the Scottish Enlightenment is about the Scottish Diaspora. There are many types of "Scots" that emigrated to different parts of the world. I'm most familiar with the Scots in America but they settled everywhere the British Empire existed. They were composed of Lowlanders (of all classes from cities such as Glasgow and Edinburgh), highlanders, and the Ulster Scots (or the Scots Irish). These groups created a "warrior culture" as well as a university culture. I have a book called Born Fighting about the Scots in America, as an aside. Somewhere in my TBR pile.

When the Scots first came to America, they brought their religion (The American Presbyterian religion has many Scottish elements and is similar to services in the Kirks in Scotland) and their educational system. Princeton was run by a Scottish man named John Witherspoon. Witherspoon was a signer of the American Independence. I found the different waves of immigrants to America from Scotland and how they responded to the American Revolution fascinating. Many of the early arrivals (like Witherspoon) were for an independent America, while later immigrants (such as Flora MacDonald) were loyalists. A popular refrain at the time was "Tories with their brats and wives, should fly to save their wretched lives." In fact, many loyalists fled to Canada or back to the U.K. The Scots were very involved in the American Revolution (on both sides) for freedom and for monetary gain. Ulster Scots seemed to join because of their hatred of the English. Something of note (to me at least) was the civilian militias created in America being of interest to the Scots at the time. Scottish civilian militias were not allowed by the British government (since Culloden and the Militia Acts of 1757), so when Scots arrived in America, they took up arms with glee (especially the Ulster Scots). Back in Scotland, Adam Ferguson became a firebrand on the subject of Scotland needing a civilian militia, eventually winning over Adam Smith. Going back to the American Revolution for a quick moment. The Scots in America were split (mostly depending on when they arrived and from where) but the Scots in Scotland were also split. Herman notes that nineteen of the fifty-six signers were Scottish/Ulster Scot extraction. Another scholar has the number as high as twenty-one. Other non-Scots were taught via the Scottish educational system set up in America. Thomas Jefferson attended William and Mary, which had switched to the Scottish model and his teacher William Small was a University of Aberdeen man. The final copy of the Declaration of Independence was written by Charles Thomson, an Ulster Scot Back in Scotland and the U.K., feelings were split. Scots were members of Parliament and two were part of Lord North's (the Prime Minister) cabinet. The Solicitor General was Alexander Wedderburn and the Lord Advocate for Scotland was Robert, Lord Dundas (I think this was a mistake as Robert, Lord D. was born in 1771 and Henry, Lord D. worked for Lord North). Opposite them in feelings was Lord George Gordon who felt the American cause was worthwhile. The merchant class was less split as their fortunes would be impacted negatively. By 1776, many of the Glaswegian merchant companies were on precarious footing indeed. The famed Scottish Enlightenment thinkers also split in feelings over the American Independence cause. William Robertson chose to stay loyal in all ways to the crown. David Hume told Benjamin Franklin in 1775 that "I am an American in my principles and wish we would let [them] alone to govern or misgovern themselves as they think proper."

Sir Walter Scott gets his own chapter. He's an important figure in the Scottish mythos because he really starts the view of the romantic Scot, we wouldn't have Outlander without Sir Walter Scott. Herman really explores the way Scott creates this historic story of Scottish history. I mean, the history is historic of course and very interesting; it's the lens that we all view it in that Scott shaped. I find Scott an interesting author and character. His house alone is stunning and worth a visit!

The chapter after these deals with Scottish science and industry with heavyweights like James Watt, William Cullen, Joseph Black, and John Roebuck. Also, the medical schooling that Scotland had brought many forward movements in obstetrics, dentistry, disease identification (Richard Bright, Thomas Addison and Thomas Hodgkin diagnosed the diseases that bear their names). More advancements in science are named in detail. I didn't know they were Scottish inventions or breakthroughs, so that was quite cool to learn. The next chapter is Scottish migration and traveling within the British Empire and even out of the Empire. With Scottish education being so respectable, many Scottish emigrants were welcome because they had skills and education. The feared ancient Scottish regiments now fought for the British crown. Herman mentions the Black Watch, they claim their creation as 1725 while others have it as 1881. At the earliest, they were a pro-English (via the Campbells, natch) and anti-Jacobite formation. Not quite the pre-English grouping that were on par with the Gallowglass. No matter, I do love their tartan, not as much as the World Peace Tartan. I digress. I've been told repeatedly by people in the U.K. that their special forces are mostly made up of Scottish and Northern Irish people. I have no idea if that's true. Mostly the Scots told me that and they might have been pulling my leg.

The rest of the book deals with Scots making their fortunes or inventions in America after the Revolution (Andrew Carnegie is one notable man). The book than transitions into the ending thesis of Scotland being the first modern culture.

Herman takes a look at the similarities in Scots in Canada and in the U.S.A. Canada and the U.S.A. have a lot in common and they also are really, really different in some ways. The Scots who chose to emigrate to Canada differ greatly from the Scots who chose to emigrate to America. Apparently, Scots who wanted to farm and live rurally moved to Canada while Scots who wanted to work in trade. What an interesting distinction! Of course, Canada had the Hudson Bay Company and the might of the British Empire being it.

Well, this was a long look! Overall, I liked the book! I think it is a bit dry in places but to be honest, a lot of philosophy is dry. It is. I like it and I find it dry.

Sometimes Herman just lists achievements instead of really expanding on them. I think because he expounds upon the education system in Scotland, he expects you to make the jump (i.e., Scotland was able to have all these inventions and medical advancements due to their fabulous educational system), but he doesn't go too much into it. Other than just providing education to the masses through their parish school system, he doesn't go in depth as to why the schools are top notch. There are a few things I disagree with. I've lived in the U.K. off and on. While I'm not an expert on their political history or even cultural shifts, there were some things I wasn't sure I agreed with. That's also me being super nitpicky. See my issues with Scottish regiments pre/post Culloden. I suppose my outlook is far more Jacobean than actual Scottish people would define it. The mix up of the Lords Dundas was unfortunate but honestly not too shocking, they both get referred to as Lord Dundas. Herman also focuses on America with Scottish diaspora. He is an American author but if you're looking for more of an international look at the diaspora, this is not the book for you. There are some quips for loyalist Scots in Canada vs, Scots in America about annexing California that made me laugh, but the Scottish-Candian experience is not explored. Overall, it's a truly interesting look at the Scottish influence on education and world philosophy. I'm not sure it's fair to blame them for America (they'd probably take offense!) but the link is a lot stronger than most would imagine. If you pick this up, be prepared to really focus on it because it's jam packed with information.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|