|

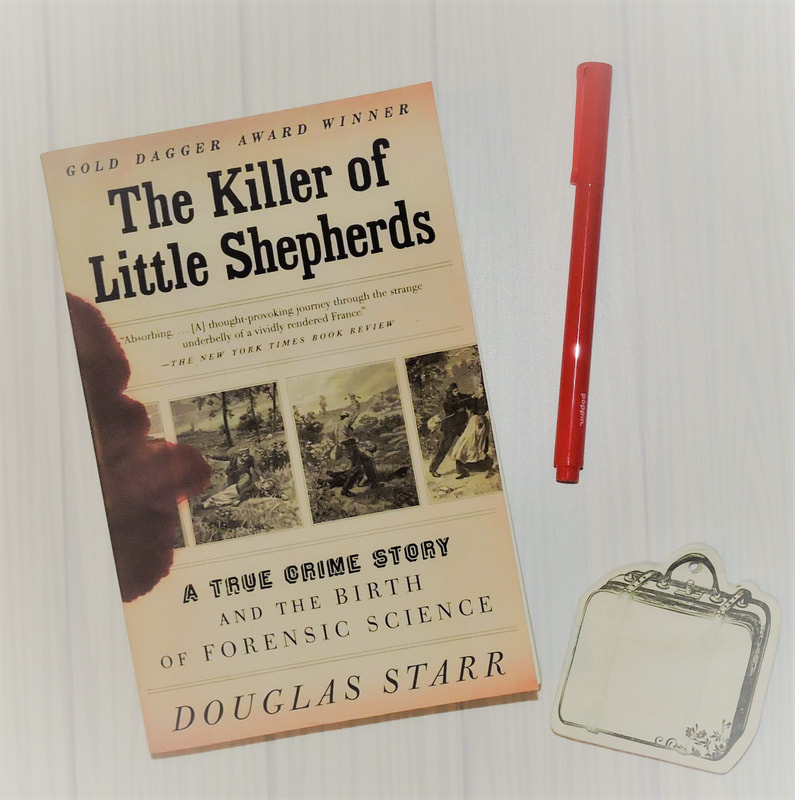

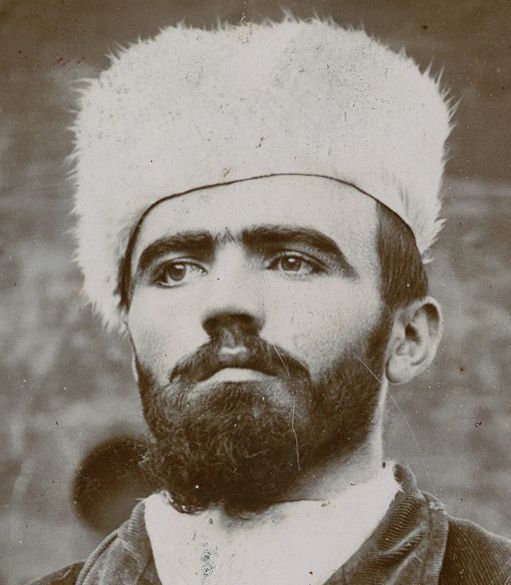

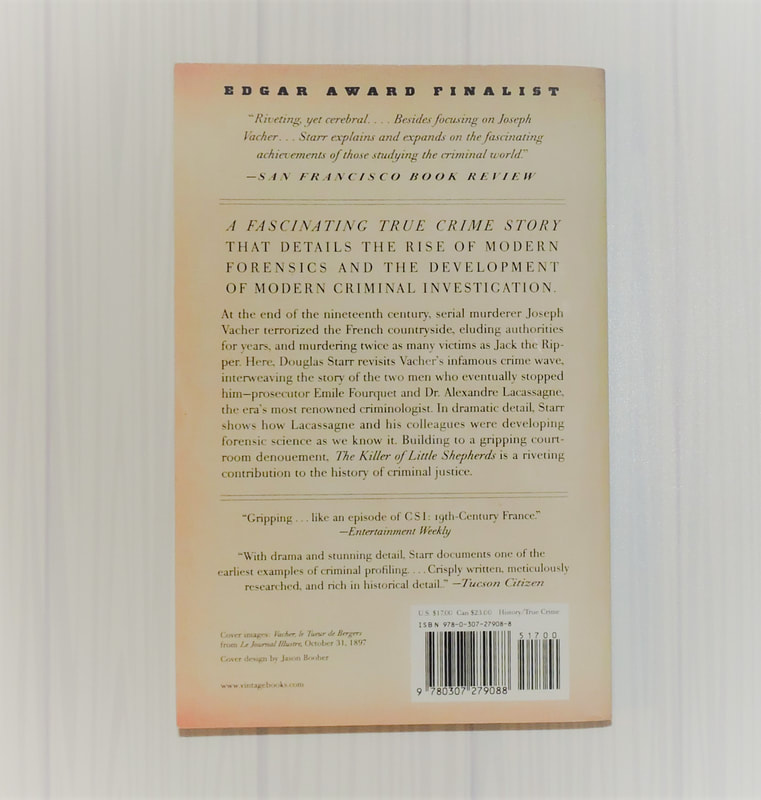

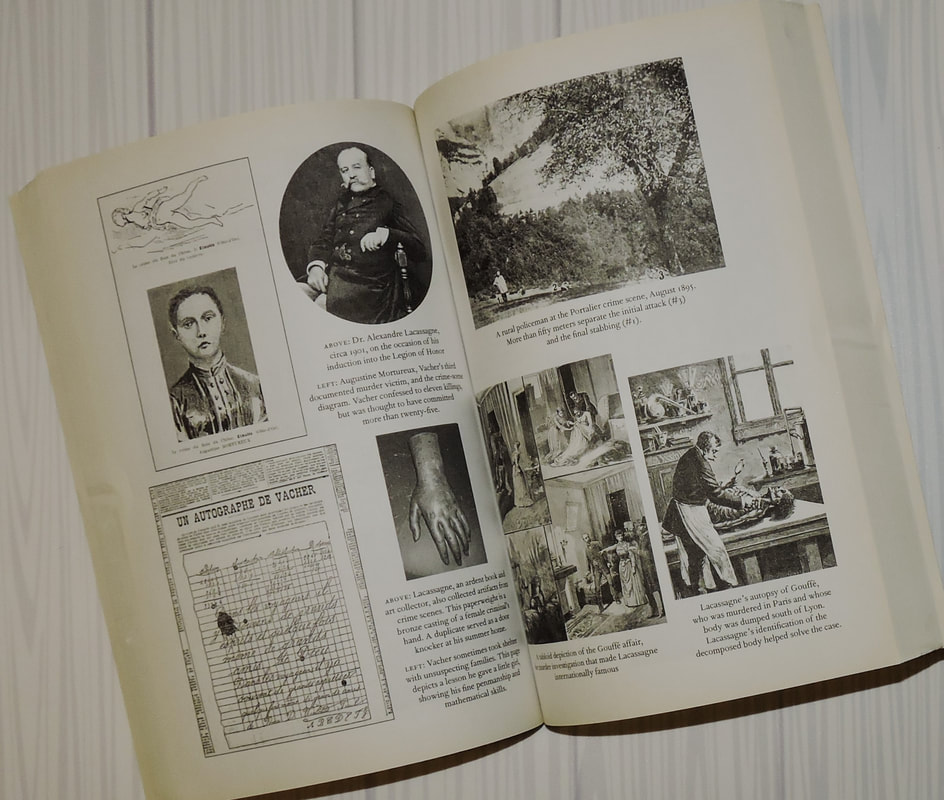

Oh, this book was a revelation! It's one of those multi-storied books. We get the story of a serial killer and his apprehension, a story on how the lawyer changed how to prosecute, and the story of how a scientist used forensics to catch the criminal. We also get to have the culture of France at the time, the history aspect really. It's one of my favorite type of book set ups. I'm not sure if it has a name. Popular History? But with this multiple arcs. That being said, it's a lot of information. Obviously, any of these aspects could fill multiple books by breaking it down in detail. I got enough to understand everything though. Douglas Starr is a new author to me. He has another book, aptly titled Blood, about how blood became valuable in the medical field. I do like my nonfiction to be science or history, so I might see if I can pick that up soon. Title: The Killer of Little Shepherds: A True Crime Story and the Birth of Forensic Science Author: Douglas Starr Page Number: 300 pages (hardcover) Genre: nonfiction, true crime, history, science, mystery Publisher: Knopf Year: 2010 At the end of the nineteenth century, serial murderer Joseph Vacher, known and feared as “The Killer of Little Shepherds,” terrorized the French countryside. He eluded authorities for years—until he ran up against prosecutor Emile Fourquet and Dr. Alexandre Lacassagne, the era’s most renowned criminologist. The two men—intelligent and bold—typified the Belle Époque, a period of immense scientific achievement and fascination with science’s promise to reveal the secrets of the human condition. With high drama and stunning detail, Douglas Starr revisits Vacher’s infamous crime wave, interweaving the story of how Lacassagne and his colleagues were developing forensic science as we know it. We see one of the earliest uses of criminal profiling, as Fourquet painstakingly collects eyewitness accounts and constructs a map of Vacher’s crimes. We follow the tense and exciting events leading to the murderer’s arrest. And we witness the twists and turns of the trial, celebrated in its day. In an attempt to disprove Vacher’s defense by reason of insanity, Fourquet recruits Lacassagne, who in the previous decades had revolutionized criminal science by refining the use of blood-spatter evidence, systematizing the autopsy, and doing groundbreaking research in psychology. Lacassagne’s efforts lead to a gripping courtroom denouement. Image: Joseph Vacher, from Bibliothèque de la Ville de Lyon, via Wikipedia. One of the people we follow is Joseph Vacher (1869-1898), a convicted French serial killer. He killed more people than Jack the Ripper, with eleven known murders. He was sadistic, incredibly brutal, and itinerant. He was raised in poverty and joined the French army in order to escape it. He seemed to have grandiose opinions of his own self-worth, believing that he should have advanced in society. He tried to kill himself a few different times. He then began to wander around the south of France, killing younger farm workers. There is a story about one of Vacher's attempts at suicide. He had fallen in love with Louise, a young woman he met while in the army. Louise was not interested in any relationship with Vacher and turned his advances down multiple times. In a story oft told with men like this, he returned to Louise's house and tried to kill her and himself with a gun. They both survived the shooting, but Louise was badly hurt and probably had PTSD her whole life. Poor thing. Vacher managed to shoot himself in the face, and the bullet stayed in his head his whole life. It left him with partial paralysis on his face. Did the shooting exacerbate his mental issues? Maybe, the brain is a complex thing. He ended up in a mental institution for recovery after this assault. Vacher spent some time in the mental institutions and we get a small information dump on the evolving science of dealing with people with mental issues (varying). It's very interesting, and I have several books that deal with this transformation in medicine. Vacher was clever and did well in the institution. He was eventually released (due to trickery or funds, it's hard to quite tell. Maybe it was considered he was driven to violence due to passion...something that still lingers. Most mass killers and serial killers have these previous incidents of violence towards women that get bargained down or ignored for reasons). He was twenty-five years old. He began is killing spree after this period. Over three years, he walked all over southern France. Killing at least eleven people (one adult woman, five young women, five young men). They tended to be in smaller, farming communities. The victims were raped, murdered, disemboweled, and otherwise slashed repeatedly. After killing, Vacher would drift on towards his next victim, often traveling miles before the victim was even found. He would often walk up to twenty miles (around 32 kilometers) a day. Putting a huge amount of distance between his crimes.

Anyways, Lacassagne was doing all this advanced medical work while most of the French forensic work was less advanced. Rural autopsies, hampered by a lack of access to more modern science, were often done on the closest dining room table, sometimes after days waiting. The way police would investigate was often crude leading whole towns to decide on mob vengeance (causing more than one family to escape to avoid being murdered). There was no instant federal (or state-wide) communication between police units, letting them realize quickly that they needed to be on the look out for a suspect. Other scientists around the world also were working in advanced (or at least researching) methods as well. Lacassagne can be compared to Cesare Lombroso, who led the Italian school of criminology. He had similar and not-similar techniques (one was phrenology). Lombroso said “Genius is one of the many forms of insanity,” which is a pretty famous quote, I believe. Lacassagne created the Lacassagne school of criminology which is considered part of the Classic school of criminology. I'm not as knowledgeable of this field, so I might be wrong on this. He consulted on many cases, some more famous than others (like the Gouffe Affair case). Much of the work used today in forensics, can be traced back to this period in criminology advancement. While not all the research done by either school (the Italian and the Classic) is useful in determining guilt, it can be used as a "well, that didn't work." The third man we follow is only introduced in the final act of the story. His name is Émile Fourquet, the magistrate assigned to investigate Vacher and his crimes. He was aware that there was a serial killer (although the term wasn't yet coined) and sent a bulletin to all the police stations in France, asking for information. This is also how he connected Vacher (other than Vacher's confession), by connecting the crimes. He noticed that many of these murders were similar in how they were carried out, with a frenzied approach. Fourquet was lucky, as the French police, rural and suburbs, kept better records than their contemporaries in other countries. So he was able to really study the previous crimes. The trial was a circus. Vacher put on a loud show, arguing with his lawyers and the prosecutors, held up placards, and yelled at anyone he wanted. This was considered an act to try and prove he was insane. He was found guilty and sentenced to death, at this time carried out by the guillotine. The time that Vacher lived was the same time of the rapid expansion of the newspaper as a medium of news/information. Newsagents were popping up (and disappearing) and often in a breakneck manner in order to capture readers. The rise of the newspaper is honestly fascinating. I have books that detail that as well as the sensationalism that brought some "news" agents to the forefront. I have a book about murder in the Victorian age in the UK that created this morbid interest in death for the Victorians. I don't have much from France about this topic, mostly because my French is so bad so I can't read without translations. Anyways, the media in France was no exception to this idea. They also realized that crime sells paper (what's the phrase, "if it bleeds, its leads"). Actual newsagents today are supposed to follow an ethics guideline. Some entertainment stations don't want to abide by these rules, so they classify themselves differently in order to be able to lie. I don't have to say who that it is. Anyways, back then, that was not the game. There were no ethics. The rule of the game was to sell. So sensationalism ruled. It was often irresponsible, leading to innocent people being named as guilty. At the trial, Vacher claimed he was insane and not able to understand what he was doing. It's the insanity defense basically. I think he might have been insane...because to kill that many people you'd have to be, but that's not how they determine stuff like that. I'm not in charge! Lacassagne was asked to determine if Vacher was insane by Fourquet. He determined that Vacher had a routine, a system, in which he picked and attached his victims. A modus operandi if you will. This was used as evidence that Vacher was able to be responsible. It was also noted that Vacher hid his victim's bodies, showing that he knew he did wrong. Vacher had claimed that he only killed when he had moments of insanity, that he was bit by a rabid dog, that the cure for the rabid dog bite caused his insanity, etc. He probably wanted to go back to the mental institutions as he seemed to do well there. After his execution, Vacher was dissected and his brain was examined. It was learned he was infected with tertiary syphilis but otherwise his brain was normal. This was a really interesting story, with lots of information. I had never heard of Joseph Vacher, Emile Fourquet, and Alexandre Lacassagne. I did know a tiny bit about forensics that developed (Vidoq and fingerprinting bother being developed in France). I guess I would say that this book wasn't as smooth as I'd like but I think it's hard to do that with a story of this size and scope. I did leave the book thinking "well, damn! That was fascinating." It's utterly fascinating and really great. While Starr does talk about the depravity of Vacher's crimes, it wasn't totally unappalling. I mean, if you can make it through the kitchen table autopsies, it's all just words on a paper. The question lingers if Vacher was crazy. Did the the syphilis or bullet cause him to commit any of these crimes? Where does criminal insanity comes from? How are serial killers formed? I think it's hard, or even impossible, to answer any of these questions. Other:

New York Times review Publisher's Weekly Review Kirkus's Review Atlas Obscura's Cesare Lombroso's Museum of Criminal Anthropology Victorian Supersleuth's French Ripper

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|